Preston, Margaret Junkin (19 May 1820-28 Mar. 1897), poet and writer, was born in Milton, Pennsylvania, the daughter of Rev. George Junkin and Julia Rush Miller. A Presbyterian minister, her father was called to Easton, Pennsylvania, in 1832 to assume the presidency of the newly established Lafayette College. As a child, Margaret was tutored by members of the Lafayette faculty as well as her parents. Dr. Junkin became president of Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, in 1841; three years later, he returned to Lafayette. In 1848, having accepted the presidency of Washington College (later Washington and Lee University), he moved his family to Lexington, Virginia.

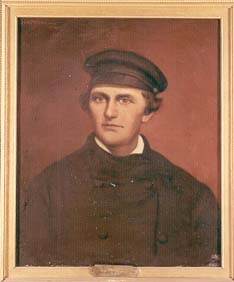

Straining her eyes by sewing and reading, Margaret Junkin had seriously impaired her vision by the time she was twenty-one. Nevertheless, after the move to Lexington, she began to publish poems and stories in newspapers and magazines. In 1856, she published anonymously Silverwood: A Book of Memories, a novel that satirized the emphasis Virginians placed on ancestry. The following year, she married Major John T. L. Preston (portrait at right), a widower with seven children, who helped found the Virginia Military Institute and taught Latin there. Margaret's sister Eleanor married Major Thomas Jonathan Jackson, later famous as "Stonewall" Jackson, who was professor of mathematics at the Institute. Margaret and John Preston later had two sons of their own.

Preston's family, like many others, was divided by the Civil War. Dr. Junkin was forced to resign the presidency of Washington College in 1861 because of his Unionist sympathies. Although Major Preston opposed secession, he went along with Virginia and served under Stonewall Jackson; Margaret Preston shared his political views. Espousing the southern cause, she wrote some of the most popular verse in the Confederacy.

In the intervals between housekeeping duties, Preston kept a wartime diary, which became the basis for her second book, Beechenbrook: A Rhyme of the War. Her husband, now a colonel, had an edition of 2,000 copies printed in Richmond in 1865. Most of this edition was destroyed during the burning of Richmond. The work sold over 7,000 copies when it was republished in Baltimore in 1866. A long narrative poem, Beechenbrook carries the reader through the war years with a southern family. In lines that were often quoted, Preston described vividly the lot of the Confederate soldier during bitter winter weather:

Preston, Margaret Junkin (19 May 1820-28 Mar. 1897), poet and writer, was born in Milton, Pennsylvania, the daughter of Rev. George Junkin and Julia Rush Miller. A Presbyterian minister, her father was called to Easton, Pennsylvania, in 1832 to assume the presidency of the newly established Lafayette College. As a child, Margaret was tutored by members of the Lafayette faculty as well as her parents. Dr. Junkin became president of Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, in 1841; three years later, he returned to Lafayette. In 1848, having accepted the presidency of Washington College (later Washington and Lee University), he moved his family to Lexington, Virginia.

Straining her eyes by sewing and reading, Margaret Junkin had seriously impaired her vision by the time she was twenty-one. Nevertheless, after the move to Lexington, she began to publish poems and stories in newspapers and magazines. In 1856, she published anonymously Silverwood: A Book of Memories, a novel that satirized the emphasis Virginians placed on ancestry. The following year, she married Major John T. L. Preston (portrait at right), a widower with seven children, who helped found the Virginia Military Institute and taught Latin there. Margaret's sister Eleanor married Major Thomas Jonathan Jackson, later famous as "Stonewall" Jackson, who was professor of mathematics at the Institute. Margaret and John Preston later had two sons of their own.

Preston's family, like many others, was divided by the Civil War. Dr. Junkin was forced to resign the presidency of Washington College in 1861 because of his Unionist sympathies. Although Major Preston opposed secession, he went along with Virginia and served under Stonewall Jackson; Margaret Preston shared his political views. Espousing the southern cause, she wrote some of the most popular verse in the Confederacy.

In the intervals between housekeeping duties, Preston kept a wartime diary, which became the basis for her second book, Beechenbrook: A Rhyme of the War. Her husband, now a colonel, had an edition of 2,000 copies printed in Richmond in 1865. Most of this edition was destroyed during the burning of Richmond. The work sold over 7,000 copies when it was republished in Baltimore in 1866. A long narrative poem, Beechenbrook carries the reader through the war years with a southern family. In lines that were often quoted, Preston described vividly the lot of the Confederate soldier during bitter winter weather:

-

Halt! the march is over;

Day is almost done;

Loose the cumbrous knapsack,

Drop the heavy gun:

Chilled, and worn, and weary,

Wander to and fro,

Seeking wood to kindle

Fires amidst the snow.

-

Only a private--and who will care

When I may pass away,

Or how, or why I perish, or where

I mix with the common clay?

They will fill my empty place again,

With another as bold and brave,

And they'll blot me out, ere the Autumn rain

Has freshened my nameless grave.

-

My brain

Dizzied and whirled with sudden pain,

Trying to span that gulf of years

Fronting once more those long-laid fears.

Confess--why yes, if I must, I must.

-

Yes, "Let the tent be struck:" Victorious morning

Through every crevice flashes in a day

Magnificent beyond all earth's adorning:

The night is over; wherefore should he stay?

And wherefore should our voices choke to say,

"The General has gone forward?"

Life's foughten field not once beheld surrender;

But with superb endurance, present, past,

Our pure Commander, lofty, simple, tender,

Through good, through ill, held his high purpose fast

Wearing his armor spotless,--till at last,

Death gave the final, "Forward."

-

May, but father, grant me now

The skill for what I can do;--curb the colt

That's wildest in your stalls,--lead on the hounds,

And fly the hawks; or from an ilex-knot,

Carve out a shrine, my sister praises more

Than Donatello's cuttings; or frame flutes

You own make music to your mind; or paint

A saint's face for some teasing servant-maid

To say her prayers to.

Biographical information regarding Margaret Junkin Preston can be found in:

- Janie McTyeire Baskervill, "Margaret Junkin Preston," in Southern Writers: Biographical and Critical Studies, vol. 2 (1903), pp. 23-45;

- F. V. N. Painter, Poets of the South (1903), pp. 25-27 and Poets of Virginia (1907), pp. 182-85;

- W. P. Trent, Southern Writers: Selections in Prose and Verse (1905), pp. 337-38;

- Carl Holliday, A History of Southern Literature (1906), pp. 294-300;

- Charles W. Hubner, Representative Southern Poets (1906), pp. 148-65;

- LaSalle Corbell Pickett, Literary Hearthstones of Dixie (1912), pp. 148-65;

- Jay B. Hubbell, The South in American Literature, 1607-1900 (1954), pp. 617-21;

- L. Moody Simms, Jr., "Margaret Junkin Preston: Southern Poet," Southern Studies, 19 (Spring 1980): 94-100.

- Margaret Junkin Preston, Beechenbrook: A Rhyme of the War, 1865 http://metalab.unc.edu/docsouth/imls/preston/menu.html From the Documenting the American South Collection, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Margaret Junkin Preston Papers Inventory (#1543), Manuscripts Department, Library of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

- Margaret Junkin Preston, http://www.civilwarpoetry.org/authors/preston.htm